Media

I Refuse to Stand By While My Students Are Indoctrinated

I am a teacher at Grace Church High School in Manhattan. Ten years ago, I changed careers when I discovered how rewarding it is to help young people explore the truth and beauty of mathematics. I love my work.

As a teacher, my first obligation is to my students. But right now, my school is asking me to embrace “antiracism” training and pedagogy that I believe is deeply harmful to them and to any person who seeks to nurture the virtues of curiosity, empathy and understanding.

“Antiracist” training sounds righteous, but it is the opposite of truth in advertising. It requires teachers like myself to treat students differently on the basis of race. Furthermore, in order to maintain a united front for our students, teachers at Grace are directed to confine our doubts about this pedagogical framework to conversations with an in-house “Office of Community Engagement” for whom every significant objection leads to a foregone conclusion. Any doubting students are likewise “challenged” to reframe their views to conform to this orthodoxy.

I know that by attaching my name to this I’m risking not only my current job but my career as an educator, since most schools, both public and private, are now captive to this backward ideology. But witnessing the harmful impact it has on children, I can’t stay silent.

My school, like so many others, induces students via shame and sophistry to identify primarily with their race before their individual identities are fully formed. Students are pressured to conform their opinions to those broadly associated with their race and gender and to minimize or dismiss individual experiences that don’t match those assumptions. The morally compromised status of “oppressor” is assigned to one group of students based on their immutable characteristics. In the meantime, dependency, resentment and moral superiority are cultivated in students considered “oppressed.”

All of this is done in the name of “equity,” but it is the opposite of fair. In reality, all of this reinforces the worst impulses we have as human beings: our tendency toward tribalism and sectarianism that a truly liberal education is meant to transcend.

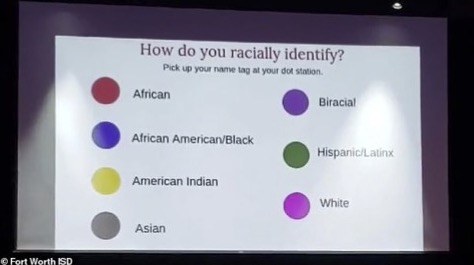

Recently, I raised questions about this ideology at a mandatory, whites-only student and faculty Zoom meeting. (Such racially segregated sessions are now commonplace at my school.) It was a bait-and-switch “self-care” seminar that labelled “objectivity,” “individualism,” “fear of open conflict,” and even “a right to comfort” as characteristics of white supremacy. I doubted that these human attributes — many of them virtues reframed as vices — should be racialized in this way. In the Zoom chat, I also questioned whether one must define oneself in terms of a racial identity at all. My goal was to model for students that they should feel safe to question ideological assertions if they felt moved to do so.

It seemed like my questions broke the ice. Students and even a few teachers offered a broad range of questions and observations. Many students said it was a more productive and substantive discussion than they expected.

However, when my questions were shared outside this forum, violating the school norm of confidentiality, I was informed by the head of the high school that my philosophical challenges had caused “harm” to students, given that these topics were “life and death matters, about people’s flesh and blood and bone.” I was reprimanded for “acting like an independent agent of a set of principles or ideas or beliefs.” And I was told that by doing so, I failed to serve the “greater good and the higher truth.”

He further informed me that I had created “dissonance for vulnerable and unformed thinkers” and “neurological disturbance in students’ beings and systems.” The school’s director of studies added that my remarks could even constitute harassment.

A few days later, the head of school ordered all high school advisors to read a public reprimand of my conduct out loud to every student in the school. It was a surreal experience, walking the halls alone and hearing the words emitting from each classroom: “Events from last week compel us to underscore some aspects of our mission and share some thoughts about our community,” the statement began. “At independent schools, with their history of predominantly white populations, racism colludes with other forms of bias (sexism, classism, ableism and so much more) to undermine our stated ideals, and we must work hard to undo this history.”

Students from low-income families experience culture shock at our school. Racist incidents happen. And bias can influence relationships. All true. But addressing such problems with a call to “undo history” lacks any kind of limiting principle and pairs any allegation of bigotry with a priori guilt. My own contract for next year requires me to “participate in restorative practices designed by the Office of Community Engagement” in order to “heal my relationship with the students of color and other students in my classes.” The details of these practices remain unspecified until I agree to sign.

I asked my uncomfortable questions in the “self-care” meeting because I felt a duty to my students. I wanted to be a voice for the many students of different backgrounds who have approached me over the course of the past several years to express their frustration with indoctrination at our school, but are afraid to speak up.

They report that, in their classes and other discussions, they must never challenge any of the premises of our “antiracist” teachings, which are deeply informed by Critical Race Theory. These concerns are confirmed for me when I attend grade-level and all-school meetings about race or gender issues. There, I witness student after student sticking to a narrow script of acceptable responses. Teachers praise insights when they articulate the existing framework or expand it to apply to novel domains. Meantime, it is common for teachers to exhort students who remain silent that “we really need to hear from you.”

But what does speaking up mean in a context in which white students are asked to interrogate their “white saviorism,” but also “not make their antiracist practice about them”? We are compelling them to tiptoe through a minefield of double-binds. According to the school’s own standard for discursive violence, this constitutes abuse.

Every student at the school must also sign a “Student Life Agreement,” which requires them to aver that “the world as we understand it can be hard and extremely biased,” that they commit to “recognize and acknowledge their biases when we come to school, and interrupt those biases,” and accept that they will be “held accountable should they fall short of the agreement.” A recent faculty email chain received enthusiastic support for recommending that we “‘officially’ flag students” who appear “resistant” to the “culture we are trying to establish.”

When I questioned what form this resistance takes, examples presented by a colleague included “persisting with a colorblind ideology,” “suggesting that we treat everyone with respect,” “a belief in meritocracy,” and “just silence.” In a special assembly in February 2019, our head of school said that the impact of words and images perceived as racist — regardless of intent — is akin to “using a gun or a knife to kill or injure someone.”

Imagine being a young person in this environment. Would you risk voicing your doubts, especially if you had never heard a single teacher question it?

Last fall, juniors and seniors in my Art of Persuasion class expressed dismay with the “Grace bubble” and sought to engage with a wider range of political viewpoints. Since the BLM protests often came up in our discussions, I thought of assigning Glenn Loury, a Brown University professor and public intellectual whose writings express a nuanced, center-right position on racial issues in America. Unfortunately, my administration put the kibosh on my proposal.

The head of the high school responded to me that “people like Loury’s lived experience—and therefore his derived social philosophy” made him an exception to the rule that black thinkers acknowledge structural racism as the paramount impediment in society. He added that “the moment we are in institutionally and culturally, does not lend itself to dispassionate discussion and debate,” and discussing Loury’s ideas would “only confuse and/or enflame students, both those in the class and others that hear about it outside of the class.” He preferred I assign “mainstream white conservatives,” effectively denying black students the opportunity to hear from a black professor who holds views that diverge from the orthodoxy pushed on them.

I find it self-evidently racist to filter the dissemination of an idea based on the race of the person who espouses it. I find the claim that exposing 11th and 12th graders to diverse views on an important societal issue will only “confuse” them to be characteristic of a fundamentalist religion, not an educational philosophy.

My administration says that these constraints on discourse are necessary to shield students from harm. But it is clear to me that these constraints serve primarily to shield their ideology from harm — at the cost of students’ psychological and intellectual development.

It was out of concern for my students that I spoke out in the “self-care” meeting, and it is out of that same concern that I write today. I am concerned for students who crave a broader range of viewpoints in class. I am concerned for students trained in “race explicit” seminars to accept some opinions as gospel, while discarding as immoral disconfirming evidence. I am concerned for the dozens of students during my time at Grace who shared with me that they have been reproached by teachers for expressing views that are not aligned with the new ideology.

One current student paid me a visit a few weeks ago. He tapped faintly on my office door, anxiously looking both ways before entering. He said he had come to offer me words of support for speaking up at the meeting.

I thanked him for his comments, but asked him why he seemed so nervous. He told me he was worried that a particular teacher might notice this visit and “it would mean that I would get in trouble.” He reported to me that this teacher once gave him a lengthy “talking to” for voicing a conservative opinion in class. He then remembered with a sigh of relief that this teacher was absent that day. I looked him in the eyes. I told him he was a brave young man for coming to see me, and that he should be proud of that.

Then I sent him on his way. And I resolved to write this piece.

California’s Education Department Chooses Critical Race Theory Over 100,000 Objections

The reason for so many objections? The curriculum continues to be founded on critical race theory (CRT), which is the view that our legal, economic, and social institutions are inherently racist and are exploited by some Whites to retain their dominance by oppressing and marginalizing others. The CRT-focused curriculum will foster divisions among students and will almost certainly not improve learning outcomes, as advertised by its proponents.

The focus on critical race theory has been severely denounced, including by the editorial staff at the Los Angeles Times and implicitly by California governor Gavin Newsom, who vetoed the second version of the curriculum. This led to the watering down of CRT over each successive revision to the point that the critical race advisors to the curriculum resigned after the second revision, complaining that—you guessed it—racist and White supremacist organizations were trying to hijack their turf.

These members wrote: “We urge the CDE not to give in to the pressures and influences of white supremacist, right wing, conservatives (‘Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies’, ‘Educators for Excellence in Ethnic Studies’, Hoover Institute [sic], etc.) and multiculturalist, non-Ethnic Studies university academics and organizations now claiming ‘Ethnic Studies’ expertise.”

CDE made a mistake by investing the curriculum in critical race theory. The CDE is unwilling to let go of this despite so many Californians believing that none of the fourth version of the curriculum is in the best interest of California students. At a time when diversity and inclusiveness are the coin of the realm within education circles, it should be apparent that ethnic studies is not an exclusive club formed by those teaching critical race theory, nor do they hold veto power in terms of who is and isn’t qualified to have a relevant idea about the subject.

In choosing to vote unanimously for the fourth version, the CDE has accepted a model curriculum with inaccuracies and omissions, as well as themes that will push students away from their own individualities and into group think that focuses on oppression and marginalization as the primary ills of today’s society. This passage from the opening paragraph says it all: “This coursework, through its overarching study of the process and impact of the marginalization resulting from systems of power, is relevant and important for students of all backgrounds.”

We should teach students world and American history honestly, openly, and with the opportunity for students to engage and understand the past with the hope that we will continue to do better, treating each other as the individuals that we are. We have had many successes in this enterprise, as no matter how flawed today’s world is, it is more democratic, civil, and peaceful than in the past.

But California’s ethnic studies curriculum differs sharply from this vision, because the narrative of critical race theory does not dovetail with a world that, on average, gets better each day. Some of the major principles of the curriculum are “critiquing empire-building and its relationship to white supremacy, racism, and other forms of power and oppression,” and “challenging racist, bigoted, discriminatory, imperialist/colonial beliefs and practices on multiple levels.”

The book refers teachers of ethnic studies to draw on the New York Times 1619 Project, which at this point has been completely discredited in terms of its arguments about capitalism, and which reflects historical errors pointed out by the Times’ own fact checker, which were ignored.

The curriculum is also flawed, and dangerously so, regarding its depiction of the War on Drugs in the 1980s and 1990s: “The dominant narrative of the ‘War on Drugs’ was that drug dealers and users were causing violence, poverty, and addiction in cities across the country. In actuality, this narrative was used to justify disproportionate arrests of communities of color, even though Blacks and Whites use drugs at similar rates.”

According to the curriculum, the War on Drugs was a racist tool to put non-Whites behind bars. Taking their argument one step further, it implies that mayors of cities, including Black mayors, chose to incarcerate non-Whites because they were . . . not White. Nowhere does the narrative describe how crack cocaine devastated poor neighborhoods in many major cities in the 1980s through the late 1990s, turning certain sections of Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans, Boston, Atlanta, New York—the list goes on—into war zones as competing drug dealers fought to control the sale of a toxic molecule that delivered enormously high profits.

Nowhere is it mentioned that the homicide rate of Black children between the ages of 14 and 17 more than doubled at the peak of these drug wars, nor that 14-to-17-year-old Blacks were 10 times as likely to be murdered than Whites during this period. Nowhere is it mentioned that the number of Black babies in foster care more than doubled, rising to a level more than six times that of White babies. How often is crack cocaine mentioned in the model curriculum? Never.

The War on Drugs did fail miserably in certain ways, including some drug sentences that were too long and inadequate prosecution of police corruption. But there are people alive today who would not be here had members from drug gangs not been arrested. Telling this part of our history—being honest and open about our country’s issues—does not fit with the narrative of critical race theory. And herein lies the major problem, and why a fourth version of the model curriculum remains unsatisfactory: because it is driven by a political and social agenda that omits the facts that inconveniently are at variance with its 24/7 narrative of oppression, imperialism, White supremacy, and exploitation.

But there is some good news. The pushback of more than 100,000 objections removed some of the most inappropriate material in earlier versions. This includes deleting positive role-model narratives about convicted murderers of police and changing the benign narrative that was originally presented about Pol Pot and the Killing Fields, where as many as 30 percent of Cambodians were murdered by his regime. The discussion of Pol Pot in earlier versions focused on how US imperialism in Southeast Asia facilitated his rise to power, not on how he was one of the of most heinous dictators of the 20th century. Go figure. Discussions about capitalism being racist, and a section that included several disturbing discussions about racial purity, also have been removed.

I doubt all these changes would have come about without the efforts of Elina Kaplan, of the Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies, Lori Meyers of Educators for Excellence in Ethnic Studies, and Tammi Rossman-Benjamin of AMCHA, all of whom have been powerful forces for providing positive directions for the curriculum. Like me, they have been called White supremacists by critical race proponents on the curriculum’s advisory committee. White supremacists? When facts and logic don’t fit the narrative, then play the race card and go right to Defcon 1: “White supremacist.” Even when they know next to nothing about any of us. But the positive here is that the alternative perspectives that Elina, Lori, Tammi, and I have been advancing are getting attention and hopefully moving the needle.

I hope these women continue to fight for California kids. We need them. And I hope that California’s school superintendent, Tony Thurmond, listens to them in the future. California schools have been chronically failing Black and Hispanic schoolchildren, as their math and reading proficiencies have been far below state standards for years. If we fix this, we will be able to fix so much more in our state, problems that will never be addressed by critical race theory.

Woke Classrooms Show Why US Parents Should Be Free to Choose on Schools

Illinois legislators last week voted in favor of enacting new “Culturally Responsive Teaching and Leading Standards” in the state’s teacher education programs.

Beginning in October, all Illinois teacher training programs must start to reflect the new standards that focus on “systems of oppression,” with teacher trainees required to “understand that there are systems in our society that create and reinforce inequities, thereby creating oppressive conditions.”

Under the new standards, all teachers-in-training are also expected to “explore their own intersecting identities,” “recognize how their identity...affects their perspectives and beliefs,” “emphasize and connect with students about their identities,” and become “aware of the effects of power and privilege and the need for social advocacy and social action to better empower diverse students and communities.”

Even the Chicago Tribune editorial board warned against the passage of these standards in the days preceding the legislative session, noting that “while the rule-writers removed the politically charged word ‘progressive’ from their proposal, there’s no doubt these are politically progressive concepts as we know them in our current national dialogue. If the rules were tilting more toward traditional concepts of teaching, if the word ‘conservative’ were peppered throughout the rules, you can imagine the uproar.”

The Tribune editors also acknowledged the “real concerns” critics have expressed toward these standards.

“Teachers could be evaluated on how sensitively they meet students’ needs, how engaged they become in political causes, rather than how much their students understand basic reading, writing and critical thinking — must-have skills to prepare any student for life,” wrote the editorial board on February 15.

Two days later, a legislative committee approved the new standards.

Critical Theory in Classrooms

The Illinois action is one example of an accelerating trend toward introducing and elevating critical theory ideology throughout US institutions, including government schools.

As Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay write in their book Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity—And Why This Harms Everybody: “A critical theory is chiefly concerned with revealing hidden biases and underexamined assumptions, usually by pointing out what have been termed ‘problematics,’ which are ways in which society and the systems that it operates upon are going wrong.”

Pluckrose and Lindsay trace the evolution of critical theory over the past half-century, from its emergence in academia to its growing influence in culture and public policy. They argue against its “illiberal” foundations that prioritize the group over the individual and that often silence free expression and dissent.

“In the face of this,” the authors write, “it grows increasingly difficult and even dangerous to argue that people should be treated as individuals or to urge recognition of our shared humanity in the face of divisive and constraining identity politics.”

The emphasis on identity politics rooted in critical theory is increasingly driving education policy, such as the new Illinois teacher standards as well as the continued push for a new high school “ethnic studies” graduation mandate in California. But it’s not just government schools that are affected by these policies.

In December, the Dalton School, a pricey New York City private prep school, made headlines when an 8-page manifesto was released demanding more attention to an “anti-racist” agenda, including hiring at least 12 “diversity and inclusion” staff members, compensating Black students who engage in antiracism activities or have their photos used in school materials, redistributing half of the private donations to Dalton toward New York’s public schools, and requiring “courses focusing on ‘Black liberation and challenges to white supremacy’ and ‘yearly anti-racist training’ for not only employees but trustees and Parent Association volunteers.”

Some parents of Dalton students removed their children from the school, including one father who told the New York Post: “It’s completely absurd and a total step backwards. This supposed anti-racist agenda is asking everyone to look at black kids and treat them differently because of the color of their skin.”

Expanding Education Choice

The same choice of exit should be open to more families who are disillusioned by what they see happening in their children’s schools. The school shutdowns and related remote learning plans implemented over the past year have given parents an unprecedented look at what their children are, or are not, learning in their schools. Many parents feel a renewed sense of empowerment and have left their district schools for private education options, including independent homeschooling which has more than doubled during the pandemic response. Other parents may want to leave their district school but lack the resources to do so.

Support for education choice policies that expand learning options for families has grown during the school shutdowns. A fall RealClear Opinion Research survey revealed that 77 percent of respondents are in favor of funding students over systems, up from 67 percent last spring.

Twenty-six states now have active legislative proposals to expand education choice and allow funding to follow students. Illinois is one of these states, with a proposal to create an education savings account program for income-eligible families that enables a portion of per pupil funding to go directly to families for approved educational expenses.

The Nobel Prize-winning economist, Milton Friedman, was an early and enthusiastic advocate of education choice policies. “If present public expenditures on schooling were made available to parents regardless of where they send their children, a wide variety of schools would spring up to meet the demand,” Friedman wrote in his book, Capitalism and Freedom. “Parents could express their views about schools directly by withdrawing their children from one school and sending them to another, to a much greater extent than is now possible.”

Parents may decide to remove their child from an assigned district school for a variety of reasons, ranging from academics to student well-being to ideology. As states like Illinois continue to push their educational institutions toward a more progressive ideology, rooted in critical theory, parents who disapprove of this ideology should have the choice and opportunity to exit in favor of other options.

“Liberalism values the individual and universal human values,” write Pluckrose and Lindsay in Cynical Theories. “Theory rejects both in favor of group identity and identity politics.”

Families that value liberalism over critical theory should be free to choose different educational options, and taxpayers who value the same should choose their legislators wisely.

[Video] Kemi Badenoch: The problem with critical race theory

Badenoch took a different view, seeing within all this a pernicious ideology that portrays blackness as victimhood and whiteness as oppression. In parliament this week, she went further: this, she said, is ‘critical race theory’ — a new enemy for the Tory party and, as equalities minister, one for her to fight.

We met earlier this month in her old workplace, The Spectator (she was our digital chief), where she reassessed her earlier stance. ‘I’d go further and say this is the best country,’ she says. ‘I’ve lived in the US, I’ve lived in Nigeria, so I feel like I’ve got some context to compare. I look at South Africa and look around Europe and ask: are those places better to be black than the UK? I don’t think so. It doesn’t mean everything is perfect… But if as a politician, especially a black politician, I don’t say this, who will?’

When she spoke in the Commons this week in a six-hour debate on Black History Month, it was quite a moment for the Tories, who, as a party, have tended to shy away from the issue of identity politics. About 30 of them offered support from the normally empty benches as she declared war on critical race theory and BLM. She added that teaching children white privilege as a fact was ‘illegal’.

‘Many people don’t realise that [critical race theory] is political,’ she tells me. ‘It’s getting into institutions that really should be neutral: schools, NHS trusts, and even sometimes the civil service.’ She is particularly incensed by the boom in sales of texts such as White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo (which claims all white people are racist and any denial of this is further evidence of racism) and Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race (whose thesis is that black history has been eradicated for the political purpose of white dominance). ‘Many of these books — and, in fact, some of the authors and proponents of critical race theory — actually want a segregated society.’ The ideas in such texts, she says, are reaching deep into large private companies and our institutions, as part of the movement to train people to be aware of their supposed ‘unconscious bias’.

She’s sceptical about such training, claiming that there’s no evidence that it works: if anyone is biased, she says, ‘You’re not going to change it within an hour’s training course.’ I point out that her own department, HM Treasury, offers this to civil servants. ‘I’ve asked to do the training!’ she replies. ‘I think there’s been enough time to have a look and see whether it’s working or not. And if it’s not, then we should remove it.’

I ask her about a recent story concerning the V&A, whose guidance for employees defines ‘black’ as ‘a term that embraces people who experience structural and institutional racism because of their skin colour’. ‘This is to politicise my skin colour,’ Badenoch says. ‘The logical conclusion of what they’re saying is that people in Africa who are not discriminated against on the basis of their race are not really black. It is associating being black with negativity, oppression and victimhood in an inescapable way. It’s creating a prison for black people.’

Black people who think like her, she says, tend not to be invited onto television. ‘There is a left-wing view of racial politics that’s assumed to be the black view of politics. Being black is not just about being a minority. On a global scale we are not a minority — but the rhetoric in this country is talking about us as if we are almost a separate sub-species.’

A Tory equalities agenda, she says, should be based on Martin Luther King’s ‘dream’ — that people should be judged ‘on the content of their character’ and not the colour of their skin. ‘Now, it’s all about the colour of your skin. That cannot be,’ she says emphatically. ‘You can’t pick and choose the rules depending on the colour of someone’s skin. That is what the racists do.’

I put to her that the Tories have dabbled in all this for quite some time, talking up racial injustice, then posing as the avengers. David Cameron notoriously claimed that a black Brit was ‘more likely to be in a prison cell than studying at a top university’. ‘There can be an issue,’ she responds. ‘In trying to show that you are a party representing all people, you accept some of the false rhetoric in order to be able to demonstrate that you’re doing something about it. But there are enough problems for us without having to create new ones…The repetition of the victimhood narrative is really poisonous for young people because they hear it and believe it.’

Badenoch grew up in Nigeria and, aged 16, won a part-scholarship to Stanford University to study medicine, but the fees were still prohibitive. She then moved to Britain where, she admits, she experienced discrimination. ‘Some very lovely liberal headteachers said: “Why don’t you try being a nurse instead? It’ll be easier for you to get it.” I would call that racism. In their minds, they were probably trying to help me because they thought: “Oh, this poor black person, she seems to be doing OK at school, let’s get her on the nursing track. She won’t fail at that. But if we give her anything difficult to do, she will fail.”’

She began a career in software engineering before joining Coutts and then The Spectator. She then stood for the Greater London Assembly before being elected to the ultra-safe seat of Saffron Walden in 2017. When she was handed the equalities brief, it surprised her friends because she has had far stronger views on the subject than her party had, historically, been comfortable expressing.

‘Too often, everyone’s waiting for the prime minister to come out and say: “This is really terrible and we’re going to do something about it.” Of course, as politicians, we have a role to play. But it can’t just be us. If you’re just waiting for your MP to say something, then you’ve lost the battle.’

Critical Race Theory divides us all

‘We do not want to see teachers teaching their white pupils about white privilege and inherited racial guilt’, said women and equalities minister Kemi Badenoch during a Commons debate this week on Black History Month. ‘And let me be clear, any school which teaches these elements of Critical Race Theory as fact, or which promotes partisan political views such as defunding the police without offering a balanced treatment of opposing views, is breaking the law.

Badenoch’s address was welcome confirmation that section 406 of the Education Act 1996, which requires teachers to be politically impartial in the classroom, applies to Critical Race Theory. Her statement should not be in any way controversial; anyone with even a cursory familiarity with CRT understands that it is fundamentally political, something that its proponents would never deny. Even so, Badenoch has predictably come under fire from identity-obsessed academics and journalists. Some have even berated the minister for opposing free speech, which simply shows that their grasp of the concept is severely limited. Like any other profession, teachers are obliged to fulfil the requirements of the job. It would be like a biology teacher refusing to cover the school curriculum, instead devoting all his lesson time to the reproductive anatomy of hens, and then declaring himself a free-speech martyr when fired for gross incompetence.

All Badenoch is saying is that political theories should not be taught as though they are incontestable, which happens to be a legal obligation. In one sense, the teaching of Critical Race Theory is an excellent idea, given that pupils should be able to understand how this divisive and destructive ideology has managed to infiltrate all of our major cultural, political and educational institutions. What better way to explore the concept of groupthink, the corruption of academia, and the bizarre phenomenon of activists who promote racial division in the name of anti-racism, than by studying a deeply flawed and yet hugely successful text such as Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility?

Critical Race Theory is underpinned by a number of suppositions. The first is that race is the defining principle of the structure of Western societies, and that ‘whiteness’ is the dominant system of power. Racial inequality is considered to be present in all conceivable situations, which is why literally anything can be problematised as racist, including breakfast cereals, the countryside, yoga, cycling, tipping, veganism, traffic lights, classical music, Western philosophy, free speech, interior design, orcs, mermaids, punctuality, beer, bras, botany, and even The Golden Girls.

Where racism is not immediately obvious, it must be assumed to be latent, and only those trained in Critical Race Theory are qualified to detect it. Often, when data explicitly show that racism in institutions is virtually non-existent, the notion of ‘lived experience’ – what used to be called anecdotal evidence – is invoked to prove the opposite. This is why the Guardian was able to run an alarmist front-page headline – ‘Revealed: the scale of racism at universities’ – even though the statistics cited in the article itself revealed that racism in higher education is vanishingly rare. Even in a society such as ours, where to be openly racist quite rightly makes one a pariah, to ask for evidence of systemic racism is taken as complicity in white supremacy.

Critical Race Theory, then, offers us an alternative vision of society, one that is pessimistic, regressive and opposed to material reality. It asks us to believe that racism is normalised and predominant, even though studies show that the vast majority of people in Britain are opposed to any form of racial prejudice. It suggests that the progress made since the civil-rights movements of the 1960s is a mirage, and that racism has been subsumed into all strata of society and that only through critical methods can it be revealed. The discourse of ‘anti-racism’ invites us to be proactive in this process of discovery. As attractive as it sounds – what kind of person wouldn’t describe themselves as anti-racist? – the concept deems activism as the only option for the enlightened. ‘There is no in-between safe space of “not racist”’, writes Ibram X Kendi. ‘The claim of “not racist” neutrality is a mask for racism.’ In other words, if you claim to be ‘not racist’ that makes you a racist.

Critical Race Theory advances a hyper-racialised approach to human interaction, one that discards the achievements of Western culture as white supremacist and essentially oppressive. This is why it favours historical revisionist endeavours such as the 1619 Project, but also seeks to ‘decolonise’ curricula in universities and schools. It is now one of the most powerful forces in public institutions. Even the British Library has a ‘Decolonising Working Group’ which hopes to review its collections and remove statues of its founders. One of the group’s more bizarre findings is that the library’s main building is a monument to imperialism because it resembles a battleship.

All of which amounts to a belief system that is as maddening as trying to ascend a staircase designed by MC Escher. Like all offshoots of postmodern thought – such as intersectional feminism, disability studies, fat studies and queer theory – incoherence is built into CRT’s core principles. The obscurantism is part of the point. It enables the well-versed to befuddle the layman with jargon, thereby giving vacuous theories the impression of substance. Activists rely on the ambiguity as a get-out clause to make statements that are bound to be interpreted as hostile. This is why Cambridge academic Priyamvada Gopal can tweet phrases such as ‘abolish whiteness’ and ‘white lives don’t matter’ and then blame those who are offended for being insufficiently schooled.

Many advocates of Critical Race Theory are doubtless well-intentioned, but that is little consolation for its deleterious effects on society. Since the death of George Floyd, numerous school authorities have embraced an ideological position that they barely understand, and teachers throughout the country have been advised to read the work of contentious authors such as DiAngelo and Kendi. Those who would deny that schools are modifying their policies in accordance with Critical Race Theory will have to explain why Channel 4 was able to make an entire documentary about a school that has done precisely that.

It will be interesting to see if Badenoch’s speech will have any broader repercussions in the corporate world or in higher education, where elements of Critical Race Theory have already been adopted as official policy, including mandatory ‘unconscious bias’ and ‘white privilege’ training. At next week’s University and College Union (UCU) conference, some of the submitted motions call for compulsory support for the BLM movement, the implementation of ‘anti-racist’ practice, and the decolonisation of curricula. If the activists get their way, it could have grave consequences for academic freedom and diversity of opinion in our universities.

Badenoch is right to clarify the legal obligations of teachers, particularly at a time when even to raise concerns about Critical Race Theory is to risk being branded a racist. As she pointed out in a recent interview in the Spectator: ‘It’s getting into institutions that really should be neutral: schools, NHS trusts, and even sometimes the civil service.’ We all share the desire to ensure that racism is challenged and defeated wherever it occurs, but this goal will never be reached through an ideology that exacerbates racial tensions and insists on division rather than unity.

[Video] Teachers presenting white privilege as fact are breaking the law, warns minister

Why Schools Are Teaching Our Kids “Social Justice”

We mistake what is, in fact, an entire worldview for a set of fringe ideas dealing with socially important issues like racism, sexism, and transgender rights. Most of us see “Wokeness,” in other words, as something that’s probably mostly good or, at worst, well-intentioned and benign.

When it comes to our children’s schools, then, many of us will conclude that it’s necessary and important in our modern, progressive world for our children to learn about these sorts of issues, and we trust our educators to communicate important truths about them so our kids can keep doing the good work of building a better society.

This kindly liberal view, borne from a combination of good intentions and being too busy to learn otherwise, misunderstands the Critical Social Justice ideology at the most fundamental level, however. It therefore completely misses the specific mission woke people—and woke educators—have for our society and our children. The crux of that mission is hiding in plain sight in the word “woke” itself, and it has everything to do with why we should be opposed to seeing these ideas featured in our educational system.

The mission of Critical Social Justice, to use its right name, is to “awaken” people to the so-called “realities” of systemic oppression in society, as it defines it—thus, “woke.” People who are woke are people who have been trained to see systemic oppression in a particular way, which has been outlined in an otherwise obscure branch of philosophy known as Critical Theory. Speaking formally, the Woke are people who have developed a “critical consciousness” about the identity-based systems of power that are alleged to permeate and define all of society, creating profound and almost intractable injustices that must be “disrupted and dismantled” to achieve “liberation.” The goal of “anti-racist,” “culturally aware,” and “social justice” approaches to education is to awaken a critical consciousness in our children so that they will grow up not to think critically but to think in terms of Critical Theories.

To understand why this isn’t just a problem but an incredibly alarming one requires understanding how the Critical Theories in Critical Social Justice see the world. That is, you have to understand what your kids will be “woke up” to in their classrooms.

To take the issue of race, Critical Race Theory begins with the assumption that racism is ordinary in our societies and present in all interactions and social and cultural phenomena, and it is up to the Critical Race Theorist—using a Woke critical consciousness—to “make it visible” and “call it out.” In Critical Race Theory, the question is not “did racism take place?” but rather, “how did racism manifest in that situation?”

Rather than learning how to do mathematics, then, your children will be taught to ask questions like how mathematics is used to maintain racial oppression—for it must, according to Critical Race Theory. This is precisely the sort of curriculum that we already see in the Ethnic Studies program in the state of Washington and its “ethnomathematics” project. Rather than focusing on the mechanics of mathematics, students will be taught to focus on the ways they can explore topics like racism and oppression through mathematics, or leaning on math as a foil that facilitates discussions on important topics—like “who it benefits” to focus on getting right answers in mathematics.

Other subjects will be similar, if not worse. A Critical Theory approach to studying American history will be dedicated to making students woke to all of the ways the United States, from its founding, has been an unjust, oppressive nation that systemically oppresses certain identity groups. This shouldn’t be understood to be part of a balanced program that reckons honestly with the darker aspects of our national past as framed against the liberal promises that eventually—and painfully—have won great freedom and equality to our diverse citizenry. It will be a sustained program of teaching our children how America is a horrible nation that has never been able to or even wanted to live up to its promise of all men having been created equally, as individuals. “Whiteness is property,” they will instruct, and that property is theft—slogans we have heard repeated as justifications for race-based riots throughout this ugly summer.

Indeed, many such programs will claim that the United States was founded intentionally on genocide, slavery, and a principle of white supremacy and anti-Blackness that has never been repaired. Its legacy is white privilege and white comfort that must be challenged at every opportunity if we are ever to achieve racial equity. Already, at least in the state of California, a proposed – although rejected – curriculum would teach these lessons not as history but as “hxrstory,” where “his” has been replaced by an explicitly “non-binary” formulation of “her,” so that maleness and cisheteronormativity won’t accidentally be centered in the term. (By the way, “his-story” isn’t even the genuine etymology of the word history, but Critical Theory looks for oppression hidden in unlikely symbols, even when it doesn’t make sense.)

Bringing Critical Social Justice into our educational systems is therefore not beneficent or benign. It is a deliberate attempt to try to program our children to think in an explicitly cynical, pessimistic, and falsely sociological way about all matters relevant to identity in every possible subject, including our history and even science and mathematics. The goal is to make our children woke, to give them a critical consciousness with which they will, unlike their parents, know that the point of understanding society is to change it in a very narrow and increasingly divisive way.

Editor’s Note: This article has been revised to clarify that a proposal to rename “history” “hxrstory” in California was rejected.

[Video] What You Need to Know About Critical Race Theory

[Video] Breaking Down Critical Social Justice Theory in K-12 Education

As they discuss, it is certainly true that most educators are just caring, engaged individuals who want to do what’s best for all their students, and it is this impulse that Critical Social Justice is manipulating to remake our education system into one of critical pedagogy for equity instead of effective pedagogy for learning.

As effectively all of our colleges of education and pre-service teacher education programs are now based on critical pedagogy—the teaching of critical theory in service of the view that “teaching is a political act”—this is a significant problem. As our education programs prepare our future professionals, leaders, and citizens, this is also an important problem.

Join Lindsay and Reusch for an animated discussion of the hows and whys behind the Critical Social Justice movement’s bid to establish itself in our K-12 education programs and beyond.

1RW.2.1.pdf

1RW.2.1.pdf